Mexican Students Didn’t Just ‘Disappear’ – Describing Them As ‘Missing’ Is Missing The Context

By Andalusia Knoll / Source: Rights Action / FAIR

The forced disappearance of 43 students from a rural teachers college in Mexico has catapulted the security crisis that the US’s southern neighbors are living into northern headlines. However, the majority of English-language news accounts have failed to provide a deeper context concerning the failed war on drugs and the use of forced disappearances as a repressive state tactic, and employ language that often criminalizes the disappeared students.

On the night of September 26th, 2014, approximately 80 students in the southwestern state of Guerrero were travelling through the small city of Iguala in a bus caravan on their way back to their teacher training college in Ayotzinapa. In Iguala they were intercepted by municipal police, who opened fire on their buses in three separate attacks, killing two students from Ayotzinapa, one teenage soccer player and two other bystanders. At least 25 people were injured, including one student who is still in a coma, and the municipal police forced dozens of the students to board their patrol vehicles.

The number of detained students totals 43; no one has heard from them since they were last seen in police custody. The following day, another student was found dead near the scene of the attack with his eyes gouged out and the skin on his face torn off.

According to the Mexican government, Iguala Mayor Jose Luis Abarca and his wife Maria de los Angeles Pineda ordered the attack, and the police handed the students over to a local drug cartel, Guerreros Unidos. Supposed gang members, who were later arrested, testified that the students were brought to a garbage dump in the neighboring town of Cocula, where they were murdered, incinerated and their ashes dumped in bags in a river. Human rights groups have expressed concern that these detainees may have been tortured during their confessions, making their testimonies questionable.

The Ayotzinapa students were unarmed and say their main defense during the attack was to drop to the ground, throw rocks to make the police stop firing or run to avoid the bullets (YouTube, 21.10.14). Yet, according to most English-language outlets, they engaged in a “violent clash.” According to BBC World (29.9.14), the “students … disappeared after deadly clashes erupted between them and security forces during a protest.” Al Jazeera America (1.10.14) basically repeated the same words: “In the aftermath of the clashes between security forces and students last week, 22 officers from the city of Iguala were detained Monday and charged with homicide.”

The students of Ayotzinapa, a school for educators of the rural poor that is historically underfunded and constantly at risk of extinction, have a long tradition of taking to the streets to ensure their school’s survival. That said, according to all eyewitness accounts, they were not protesting education reforms that day, nor protesting local politicians. In fact, the students were all freshmen and largely unaware of the politics of the mayor who allegedly ordered the attack, fearing that the students would interrupt a public event hosted by his wife.

According to the New York Times (29.9.14), the disappeared students had “been missing since Friday when gunmen fired on a demonstration they were attending.”

Why do most media outlets inaccurately characterize the events in Iguala as a protest or demonstration? Because they pulled their staffers out of Mexico long ago due to budget cuts, and therefore instead of interviewing survivors or eyewitnesses have echoed misinformation in AP pressers (e.g.,Guardian, 29.9.14).

Various media outlets attempted to explain the police attacks as a result of the student’s commandeering of commercial coach buses. A New York Times article (18.10.14) claimed that the students had been organizing an October 2nd, 2014, protest against cuts to their state-financed school, but they appear to have gotten into a skirmish with the police when they tried to steal buses to travel to and from the demonstration, human rights groups said.

According to Ayotzinapa students, they commandeer buses because their school does not have sufficient vehicles nor the funds to rent them. In recent years they have reached an agreement with two bus companies in Guerrero, who lend their buses and drivers to the students as long as they take good care of them. According to one student interviewed for this article, they already had an agreement with the bus companies for that night, and had travelled to Iguala to retrieve the vehicles.

The Spanish word “desaparecido” does not directly translate to “missing,” although that word is commonly used to refer to the 43 Ayotzinapa students. At times, “desaparecido” is more correctly translated to “disappeared,” but often it is said students “disappeared,” as opposed to “were disappeared,” as if they mysteriously vanished rather than being forcibly taken away, which is what the word actually connotes. Simply saying people “disappeared” rips the word of its context, separating it from the tens of thousands of people whose fate is still unknown due to dictatorial rule in Latin America and the war on drugs in Mexico.

The official number of disappeared people in Mexico is often cited in Mexican and international media as around 20,000, but a National Human Rights Commision report says 42,300 people are missing. This doesn’t include the thousands of migrants who cross Mexico yearly, many of whom are kidnapped or disappeared, nor the cases that go unreported. A February 2013 Human Rights Watch report detailed 149 forced disappearances at the hands of state agents during former Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s term (2006-12). Federico Mastrogiovanni, an Italian journalist based in Mexico, in his new book Neither Alive, Nor Dead, calls forced disappearances a strategy of terror. They are characterized, he writes (Mexico Voices, 29.10.14), by “the intervention, direct or indirect, by action or by omission, of public officials.”

In Iguala, the city where the students were kidnapped, residents have reported hundreds of disappearances over the past few years, and nothing had been done to address the situation.

NBC (5.11.14) mentioned disappearances, but not the government’s involvement in a large percentage of the cases: “Last year, federal authorities had said that more than 26,000 people had disappeared between 2006-2012 in Mexico, although it was unclear how many of those cases were linked to cartel violence.”

Additionally, almost all US media outlets fail to mention Guerrero’s “Dirty War” in the 1970s, when the government and army waged a battle against emerging guerilla forces, disappearing hundreds of people believed to have been part of insurgent groups. The official documents detailing the government strategy were released in 2006, and according to Kate Doyle, director of the Mexico project of the National Security Archive, they contain “dozens and dozens of pages of the names of people picked up by the police and tortured and disappeared.”

In Mexico, it’s hard to hear academics and activists speak about Ayotzinapa without referencing the “Dirty War,” yet this dark era in Mexican history receives almost no mention in US mainstream press.

Over the past two months, the Mexican government has changed its version of the attack on the Ayotzinapa students at least three times. First they claimed the students were marched up hillsides in Iguala and forced to dig their own graves, then they said the students were killed and dumped in a garbage dump in Cocula, and then, in another version, they were killed and incinerated in a separate garbage dump in the same town.

On December 6th, 2014, an independent Argentine forensic team confirmed that the remains found in one of the bags of ashes belong to Ayotzinapa student Alexander Mora Venancio. However, this forensic team, along with the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center, said that they were not present for the discovery of the bag and could not confirm that it came from the Cocula garbage dump.

The parents of the disappeared students, human rights organizations and the Ayotzinapa students have repeatedly stated that they will not believe that the other human remains belong to the other 42 students until they have been identified by the same Argentine forensic team.

But prior to the confirmation of Mora Venancio’s body, US media outlets had already taken the 43 students for dead. An AP piece (11.10.14) says, “In the case of the missing students, many of the bodies in the mass grave were burned,” even though these bodies didn’t belong to the students.

“The massacre of 43 students from a teachers college in Ayotzinapa has horrified Mexico,” writes Enrique Krauze, in a New York Times opinion piece (10.11.14) giving weight to the veracity of the government version of events. According to Mexican security analysts, Guerreros Unidos is a drug cartel that traffics heroin across international borders. US media, however, continually refer to them as a “drug gang.” This diminishes both their international scale and the power they wield within the Guerrero state government.

“The killers in Iguala were not drug gangs,” writes Dawn Paley, a Canadian writer based in Mexico. She urges her readers to recognize who the agents were who fired on the students: “They were cops and paramilitaries. Paramilitaries are non-state armed groups who work with state forces. There can be no clearer example of the horrors of state and paramilitary violence than what has happened to these students.”

“These organized crime groups are the armed wing of the government, and do the dirty work that they themselves would not do,” Abel Barrera, director of the Guerrero- based human rights organization Tlachinollan, told Extra!.

Reports have sometimes mentioned how drug cartels seem to possess more power than the government, but fail to note that in various municipalities in Guerrero government officials are actually members of drug cartels.

In social media and in the streets, many Mexicans have called for the resignation of President Enrique Pena Nieto due to his slow and ineffectual response to the crisis. But various outlets portray the issue as primarily a distraction from his neoliberal agenda, as in the AP headline (10.10.14), “Killings Drag Mexico’s President Away From Focus on Economic Reforms.”

As time goes on, the foreign coverage of the Ayotzinapa case has improved, with international press featuring more critiques of the government and a deeper analysis of security in the country. The majority of articles, however, still lack a deeper understanding of the drug war, the corruption and ineptitude in all levels of the government, and the continuing police repression that surrounds the protests.

The family members of the missing students and the Ayotzinapa classmates will continue to demand that their comrades be returned alive. Hopefully their voices, clamoring for justice, will be more centrally included in English-language press.

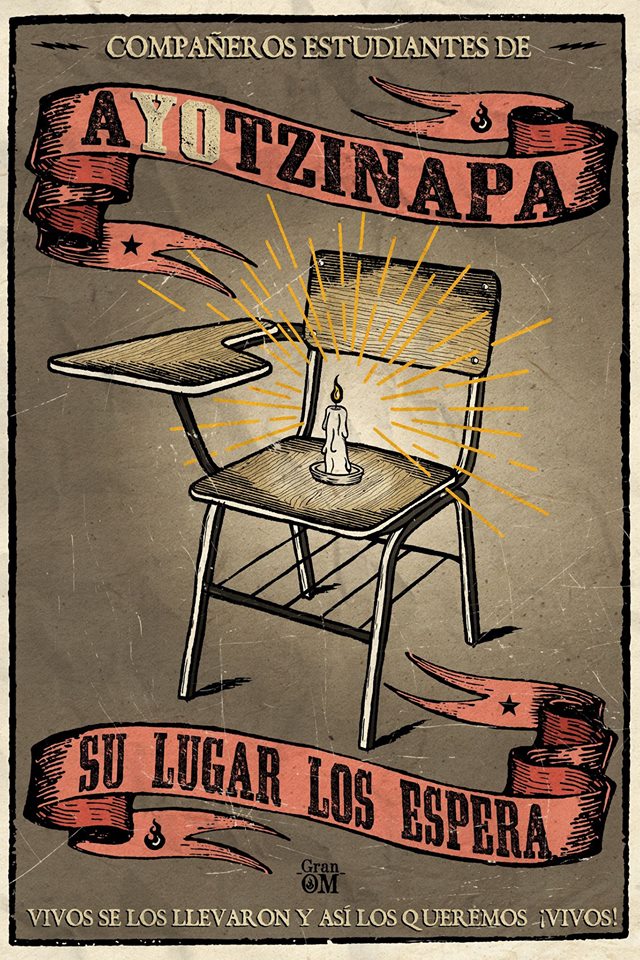

Poster, video and foto: Gran OM

Another article with strange and sad news: https://news.vice.com/article/mexico-says-missing-students-case-is-solved-despite-no-new-evidence?utm_source=vicenewsaunzfb

Hier ist ein Link zu einem Bericht im Ersten. Endlich haben sich Medien in Deutschland auch mal dem künstlerischen Protest gegen die Machenschaften in Mexiko angenommen: http://www.daserste.de/information/wissen-kultur/ttt/sendung/mdr/2014/sendung-vom-22022014-124.html

Und nun entschuldigt sich auch ein Regierungsbeauftragter für das Vorhandensein von deutschen Waffen in dieser traurigen Angelegenheit: http://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/mexiko-studenten-115.html